Modernism

Modernism (from the French moderne modern), the general name of the directions of art and literature of the late 19th and 20th centuries. In a broad sense, it embraces cubism, dadaism, surrealism, futurism, expressionism, abstract art, functionalism, etc. New artistic trends usually expressed themselves as art in the highest degree “modern”, hence the name itself.

Modernism (from the French moderne modern), the general name of the directions of art and literature of the late 19th and 20th centuries. In a broad sense, it embraces cubism, dadaism, surrealism, futurism, expressionism, abstract art, functionalism, etc. New artistic trends usually expressed themselves as art in the highest degree “modern”, hence the name itself.

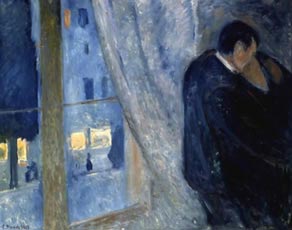

At the end of the 19th century, artists, especially impressionists (impressionism), began to organize their own exhibitions, traders began to play an increasing role in popularizing their art.However, for many, the concept of “Modernism” is associated primarily with the 20th century. The idea that painting and sculpture should truly reflect real objects and phenomena was thoroughly undermined by artists such as Gauguin and Munch, and in the early 20th century was finally overthrown by such trends as Fauvism, Expressionism and Cubism. The latter was the most radical and influential, since it contributed to the development of other trends, including abstractionism. Dadaism, which arose during the 1st World War, questioned the very essence and significance of art. It was these doubts that led to the birth of conceptual art, which put the idea, rather than execution, at the forefront. Despite the aspiration of Modernism to bring its own “order” into the theory of art, traditional painting maintained its position and the man still remained at the center of her attention.

Modernism embraced all forms of creativity, but an inspiring example of literature and music (S. Baudelaire in France, R. Wagner in Germany, O. Wilde in England) was particularly important. Although Paris in the second half of the 19th century. strengthened its authority of the world art center, the role of leaders is increasingly performed by masters of other countries. So perhaps the main forerunner of modernism in literature was the American E. Poe, and later the new Scandinavian literature (G. Ibsen and others) became its benchmark in drama.

It is at this historical moment that Russian literature (primarily in the person of F. M. Dostoevsky, L. N. Tolstoy, and A. P. Chekhov) acquires world-wide spiritual resonance; in contact with modernism, it somehow powerfully stimulates his quest.

Striving for a universal union of culture, art enthusiastically interacts with philosophy (the example of such thinkers as A. Schopenhauer and F. Nietzsche became fundamental for modernism as a whole, and V. S. Solov’ev for Russia). In parallel, the dialogue of art and religion begins; initially taking a new artistic trend critically, traditional denominations then more and more often enter into an alliance with artists, giving rise to different national versions of the “church modern”. However, with difficulty fitting into the role of the humble servant of the Church, modernism is more willing to produce its own beliefs and cults.

In the future, created by modernism “hotbeds of beauty” are perceived in the historical perspective of the 20th century as symbols of a common European “beautiful era”, whose aesthetic harmony collapsed during the First World War. The real processes of social disintegration also undermine the positions of modernism itself, they are subjected to merciless criticism in the avant-garde culture.

Nevertheless, with all this confrontation, modernist art remains the main source of the artistic avant-garde (diversely anticipated in the works of post-impressionist masters), later more than once (primarily in Art Deco) forming a stable union with it.