Antique Cologne

Cologne … Many have heard about this German city on the Rhine, a major center of medieval European culture. The well-known Cologne Cathedral is an unsurpassed monument of Gothic architecture. Its spiers, like gigantic petrified conifers, rush into the sky to a height of one and half meters. Unusual history of construction. She began to be erected in 1248. In the middle of the XV century, work stopped, and only in the XIX century, construction was completed.

Cologne … Many have heard about this German city on the Rhine, a major center of medieval European culture. The well-known Cologne Cathedral is an unsurpassed monument of Gothic architecture. Its spiers, like gigantic petrified conifers, rush into the sky to a height of one and half meters. Unusual history of construction. She began to be erected in 1248. In the middle of the XV century, work stopped, and only in the XIX century, construction was completed.

But few people know that a more ancient structure, in the place of which the majestic cathedral was erected, existed since the 9th century. It was built in the era of the Carolingians, here already in the period of early Christianity (IV – VI centuries) the church stood, and it, in turn, was built on the foundations of the ancient temple. So, gradually unraveling the complicated tangle of the history of the cathedral, we will come to ancient Cologne. Like other cities in Europe – Paris, Lyon, Marseille, Trier, Bonn – it has its history since the time of the Roman Empire.

The name of the city itself is Roman. “Cologne” means “colony”, a settlement of Roman citizens, primarily soldiers, in lands far from Rome. “Colony – Cologne” – the abbreviated name of the city, spread in the early Middle Ages. The Romans called him “Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium”. This meant that the colony was founded by Emperor Claudius on the spot where his predecessor, commander Mark Vipsanius Agrippa, friend and son-in-law of Emperor Augustus, founded a settlement with an altar. Such “altars of the world” were altars in honor of the Roman gods. These are the first centers of Roman civilization in the conquered territory.

There was no time in this corner of the Rhineland the German Eburonian tribe lived, but it was destroyed in the conquests of Julius Caesar in 53 BC. Fifteen years later, Agrippa moved a tribe of murders here from the other side of the Rhine. They and the Romans came to form the basis of the population of the Colony of Claudia.

Caesar’s sword was one of the most precious relics of the city. We learn about this by reading the colorful “Life of the Twelve Caesars” by the Roman historian Suetonius. In April 69 AD, a fierce struggle broke out between the two contenders for the imperial throne – Oton and Vitellius. Unlucky Otho had to commit suicide. Vitellius, who was in the Colony, donated the sword of the fallen opponent to the temple of the god of war Mars. He himself was proclaimed emperor: “… the soldiers, regardless of either the day or the hour, one evening suddenly dragged him out of the bedroom, greeted him with the emperor and carried him to the most crowded villages. In his hands he held the sword of the divine Julius from the sanctuary of Mars, filed by someone at the first congratulations. ”

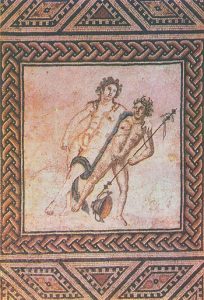

What was the ancient Cologne? The answer was excavation. Like most cities of “colonial” origin, it is planned according to the type of the Roman military camp. It was based on two streets intersecting at a right angle, “cardo maximus” and “decumanus maximus”. The first went from north to south, the second – from east to west. Curiously, this layout is still traced in modern Cologne. The city had a strong defensive wall with 9 gates and 22 towers. In the center was the Pretorium, the building where the highest magistrates of the city met. There were temples in honor of the Roman gods – Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, revered in the Roman Capitol, Mapsa, Mercury. There were luxurious public baths (terms) and an amphitheater, not yet found by archaeologists, but certainly existing – images of circus performances and gladiator fights found on the products of Cologne masters. In addition, a remarkable monument was found – a large mask made of baked clay. Such grotesque masks, painted in red, were worn by actors, speaking at cult games in honor of local gods. On the outskirts of the city were crowded quarters of artisans – glassblowers, pot makers, sculptors, wood and bone carvers, jewelers, and painters.

Numerous roads connected the Colony of Claudia with the territory of the neighboring Germanic tribes. She maintained lively connections with other cities — the forerunners of modern Trier, Mainz, Bonn. Behind the city wall, as well as along the Roman Via Appia, there were “cities of the dead” – cemeteries and necropolises. It was forbidden to bury in the city, and the roads made it possible for the living to “communicate” with the dead – their faces looked from the tombstones at the travelers. Epitaphs resurrected forgotten names.