Diego Rivera – the great Mexican painter

When the Great October Socialist Revolution took place in Russia, a revolutionary struggle was going on in Mexico for seven years. Armed peasants opposed the dictatorship of the rich and the priests, the landowners who seized fertile land, against the domination of foreign capitalists. The war was unusually stubborn and fierce. The reactionary militia malice, American troops twice invaded Mexico. The bourgeoisie traitorously turned its weapon against the peasant detachments, which were led by the popular leaders Francisco Villa and Emiliano Zapata. The rebels showed heroism and scored remarkable victories.

When the Great October Socialist Revolution took place in Russia, a revolutionary struggle was going on in Mexico for seven years. Armed peasants opposed the dictatorship of the rich and the priests, the landowners who seized fertile land, against the domination of foreign capitalists. The war was unusually stubborn and fierce. The reactionary militia malice, American troops twice invaded Mexico. The bourgeoisie traitorously turned its weapon against the peasant detachments, which were led by the popular leaders Francisco Villa and Emiliano Zapata. The rebels showed heroism and scored remarkable victories.

In February 1917, a constitution was adopted. Part of the landowner’s land was transferred to the peasants. There were decades ahead of a difficult and difficult struggle, but the Mexican revolution of 1910–1917 became an important political school for the working people: a communist party soon arose in Mexico, with which the activities of the country’s greatest artists were connected.

In the 1920s, the events of the Mexican Revolution responded with an unusually powerful rise of art. Very soon, the leaders of the art of Mexico received worldwide fame and moved into the ranks of the progressive culture of the XX century. These were Jose Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera. The first of these, Orozco, painted the watercolors “Mexico in the Revolution” (1913–1917), where he recorded the massacres of the reactionaries with revolutionary peasants. Siqueiros was an officer and an active participant in the revolutionary movement. In 1921, he delivered a manifesto proclaiming the connection between art and revolution. Becoming at the head of the new movement was natural for both artists.

The fate of Diego Rivera was different at first. He was born in the picturesque town of Guanajuato, located in the mountains. A boy from a well-to-do family, Diego, from childhood, observed the customs of the Mexican mining regions, knew the remarkable folklore of the country, and was well versed in ancient crafts. He went to a good school, he studied in Mexico City at the Academy of San Carlos. Among his teachers was a wonderful master of landscape, one of the creators of national art, José Maria Velasco. The young artist continued his education in Paris. Until 1921, he lived in Europe – mostly in Paris, but also in England, Italy, Spain, returned to war-ridden Mexico and again left for France. He brilliantly writes still lifes, bold and fresh in color, beautifully paints, and his works are a success. It would seem that the future career of the young star of the “Paris School” is fully secured. However, in the fate of a talented artist, there is a turn, at first glance, an unexpected, but natural for a responsive Mexican, sensitive to contemporary revolutionary events.

Rivera in 1921 returned to his homeland, and what is happening there captures him completely. The newly adopted progressive constitution, talented, enterprising people in the leadership, exciting initiatives in the field of culture and public education inspire creative young people. Schools and libraries are opening in Mexico, enthusiasts are going to distant villages to teach children, and artists are also striving to serve the enlightenment of the people. Art is created that is understandable and close to ordinary people, which brings ideas of social liberation and the necessary knowledge; the walls of public buildings seemed to be its natural place.

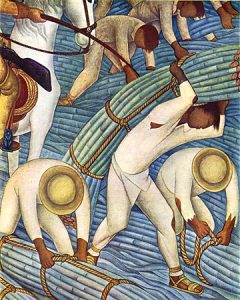

Monumental painting was seen as a kind of textbook of life, agitator and propagandist, it needed a language that was accessible to every illiterate poor man. Diego Rivera studied Renaissance painting in Italy, he knew the great power of the impact of this art and was ready to use Renaissance techniques for educational and educational purposes. But it was clear to the artist and his friends that the Mexican peasants, more familiar with a gun and a long machete-knife than with a book and a notebook, would more easily perceive artistic images in their close understanding of the Mexican tradition than in the European. Therefore, national masters of murals study and process the techniques of ancient Mexican art. You can often read that Rivera and his friends used the motifs and composition of the ancient frescoes of Mexico. But such murals were discovered in the jungle in the south of the country only twenty years later. The painters of the 1920s wonderfully guessed their style, although they knew mostly paintings on ceramics, drawings and reliefs, and even the works of modern “folk Indian masters who painted the walls of houses and courgettes,” pulkerias. “